On November 9, 1989, a wall that had divided the peoples of the East and the West in continental Europe (and around the world) since the early years following WWII came tumbling down.

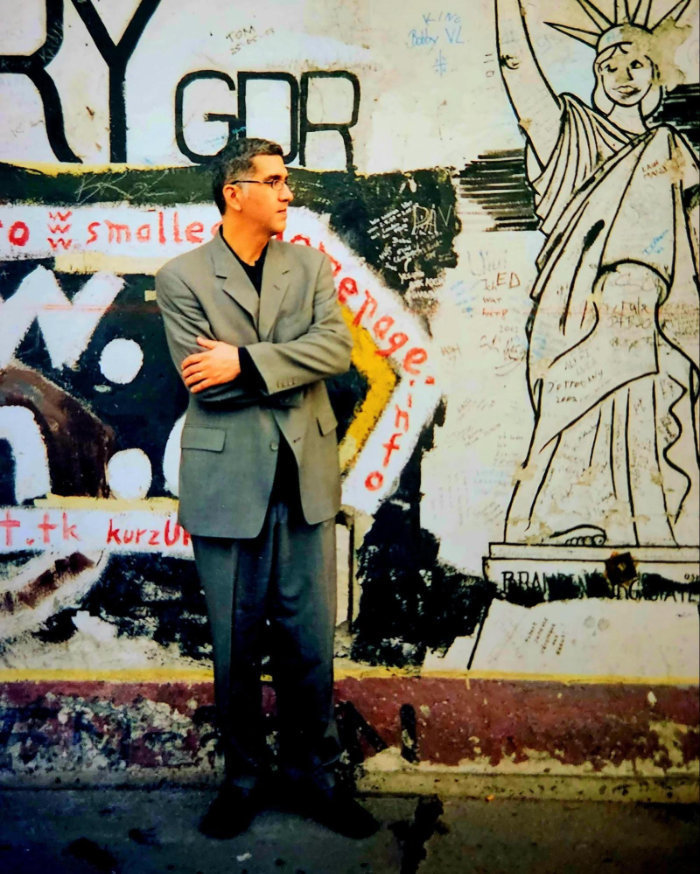

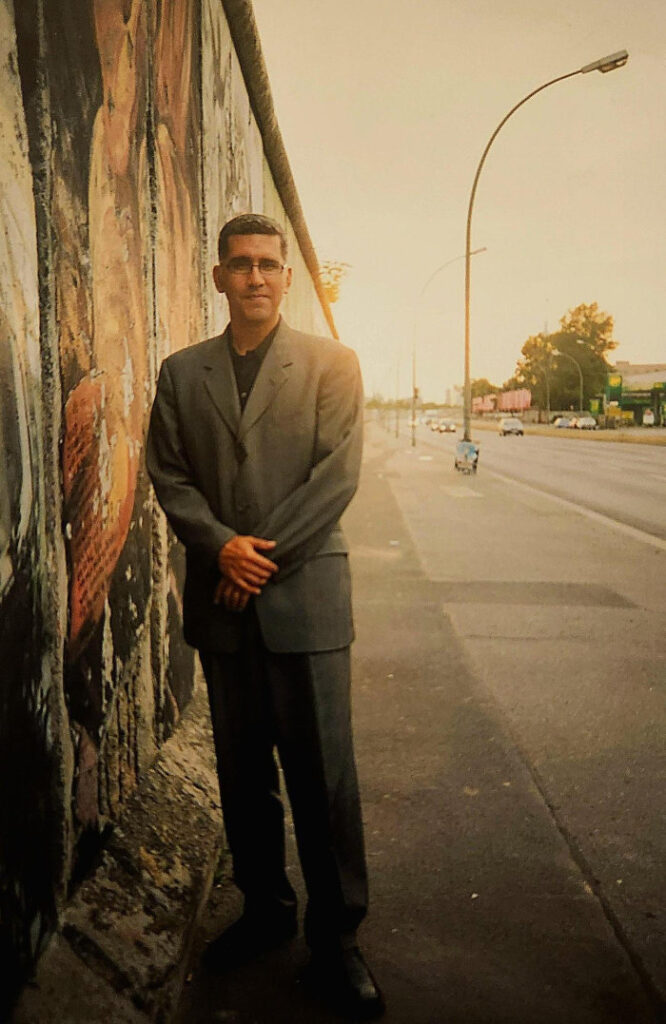

For nearly five decades, the Berlin Wall had stood as a symbol of state-imposed repression. On its western side, artists, students, activists, and average people had long shown their displeasure with the divisions between East and West. They painted graffiti all along the wall, stretching for miles, to reveal to the world in words and images what it meant to express dissent in the face of official repression and to demonstrate their solidarity with the people restrained behind its concrete.

In effect, the graffiti all over the Wall was a visible manifestation of the best of democracy. It underscored the will of the people and their freedom to actively register their deepest passions about the state of the world and their vision for a better future.

The fall of the Berlin Wall was one of the most significant and yet unexpected developments of the 20th century.

The Wall’s demise–referred to by the Germans as ‘die Wende’ (that is, the Turn)–on that fateful November day, saw citizens of the formerly-restricted Soviet Bloc of Eastern European nations flow across the borders of then East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Hungary, and Romania into Western Germany in large numbers, following years of growing internal and external resistance to Soviet-imposed domination.

It happened, most suddenly, unexpectedly, and with relative ease, as both the Eastern Bloc nations and the Soviets found themselves overwhelmed and finally unable to stem the tide of literally tens of millions of people seeking freedom in the West.

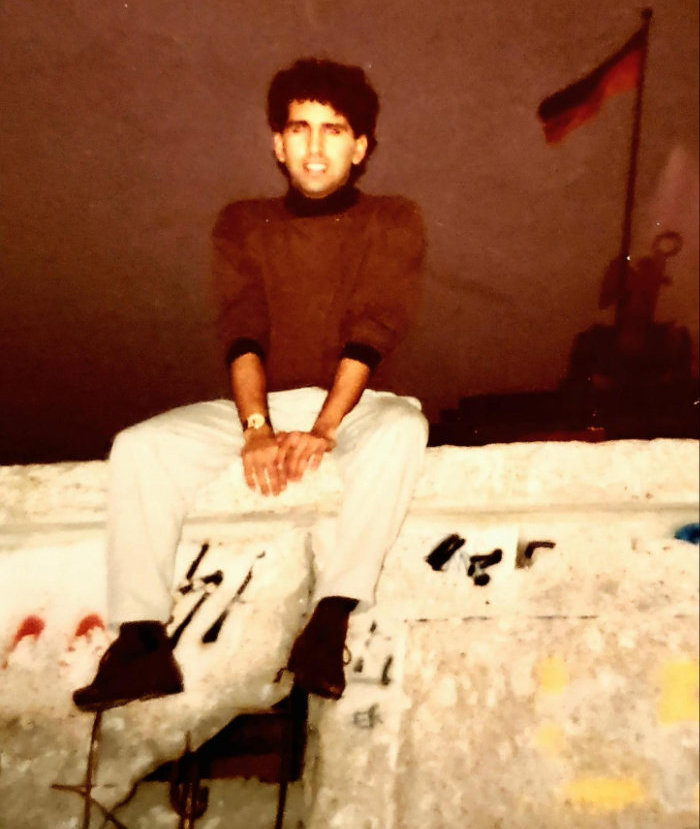

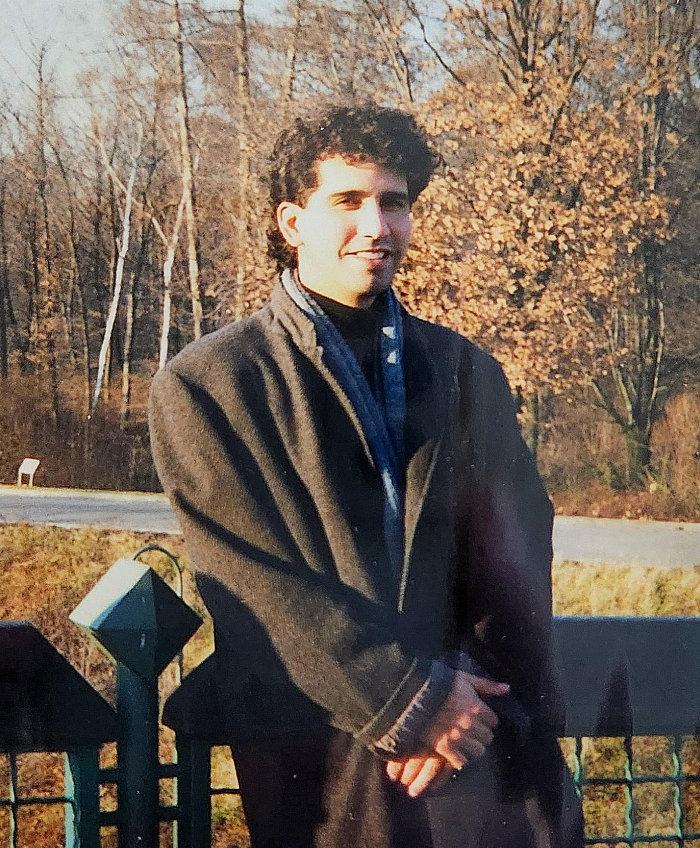

When all of this occurred, I was in the incipiency of my life-long love affair with my wife, Claudia Lenschen, a beautiful young German woman who I had met while I was studying abroad as a UC Berkeley Law School student.

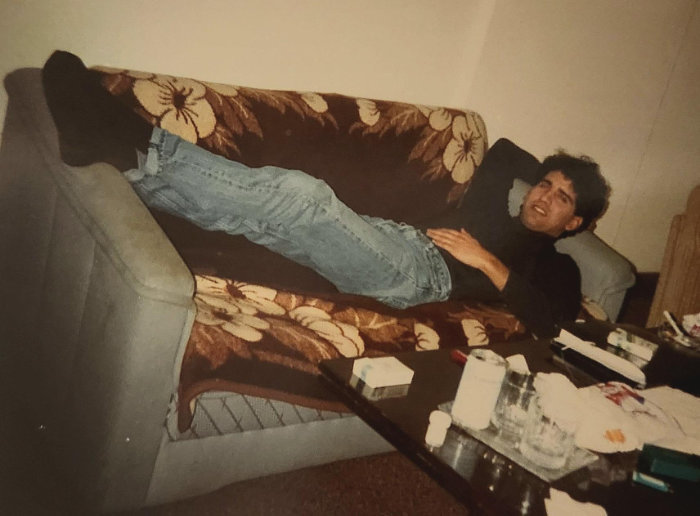

Through mutual friends, I met Claudia in Geneva, Switzerland in the Summer of 1988. We quickly fell in love and I found myself living with her family in late 1989, while I wrote a long law journal article on human rights and refugee policy in Switzerland.

Alas, when the Wende came during this early passage in our shared story, Claudia and I agreed that we absolutely had to go to Germany to explore for ourselves how the massive transformations of the day were affecting people on both sides of the divide.

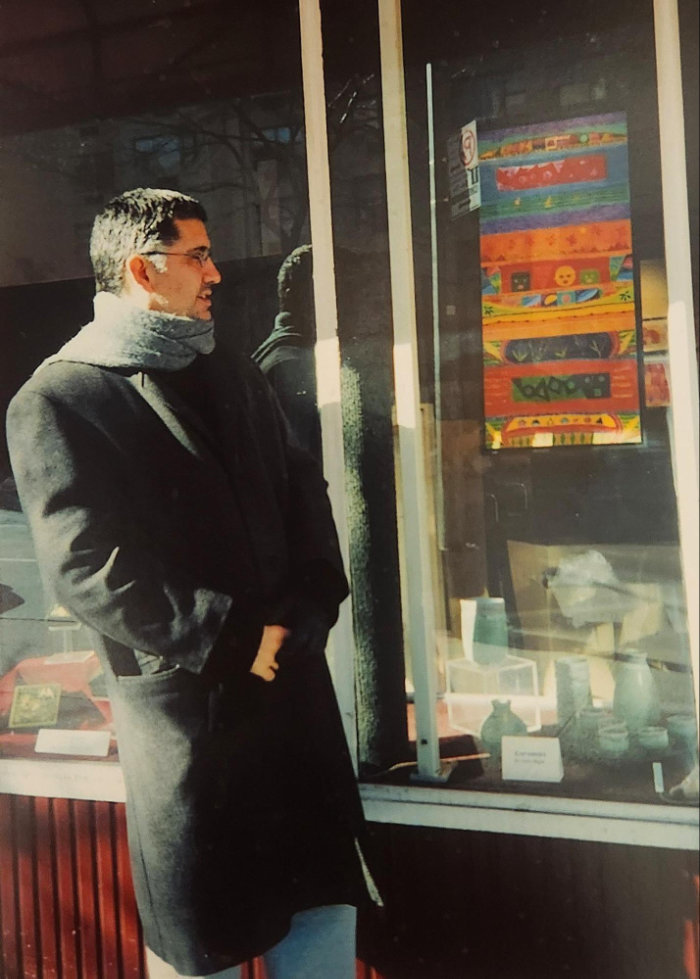

In early February 1990, we were finally able to put our work and studies aside to travel to Berlin. It was a life-reshaping journey that left an indelible mark on so many aspects of our path forward, even to this very day.

In Berlin, we stayed in the western zone on the famous Kurfürstendamm Boulevard (known to the Germans as the Ku-Damm). The place was appropriately named Hotel des Westens (Hotel of the West), and it was perfectly placed for my first-time visit to Germany’s greatest city.

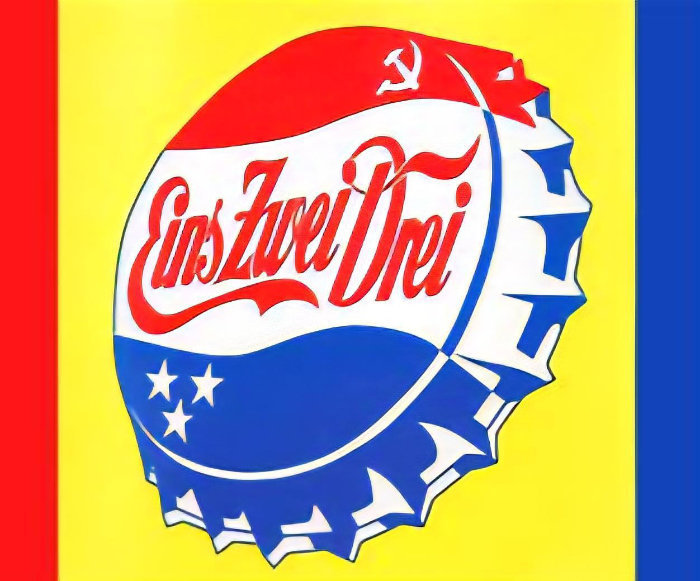

From the hotel, we had quick access to the Brandenberger Tor (the Brandenberg Gate) and Check Point Charlie, two renowned dividing points between the east and the west. We were also close to the beautiful Tiergarten Park and the Teater des Westens (Theatre of the West), where we caught a thematically well-timed live performance of the play, “Eins, Zwei, Drei,” that had been adapted from the 1961 film by Billy Wilder, called “One, Two, Three.”

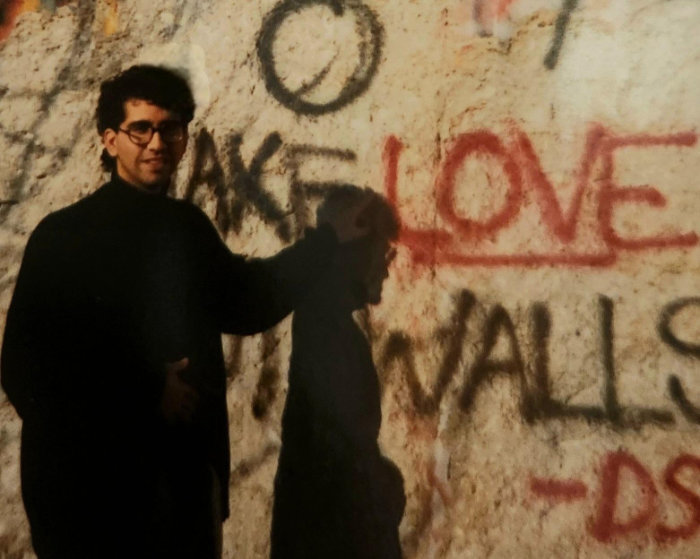

Above all, our location in Berlin situated us close to the Berlin Wall and important access points to East Berlin. So, naturally, we took advantage of that and spent a lot of time checking out the amazing political graffiti on the Wall–known to the locals as ‘die Mauer,’ as well as important points of interest ‘on the other side.’

My first peeks at the Wall were utterly transformative. I was moved, mesmerized, and motivated all at once! Unlike anything else I had ever experienced, die Mauer singularly captured my core passions for purposeful art and politics.

Most of the words and images that adorned the Wall were cheeky, snide, sarcastic, and hilarious. They cleverly mocked communism and the clear failures that were rampant in the East.

But some of the entries on the Wall were more serious. They made you think. Some made you want to cry.

My favorite was an artful design accompanied by the words, “Make Love, Not Walls.”

It was funny, meaningful, and emotional all at once for me.

When Claudia and I finally decided to cross over the Wall to visit the East, we were informed that we could not cross together.

Claudia, being a German citizen, had to cross at one checkpoint. I, being American, required a separate crossing through Checkpoint Charlie.

Having to separate and conjure a plan to meet on the other side, in such a foreign and historically hostile place was suddenly a serious reminder of what we were dealing with–a system of repression and surveillance.

As we respectively found our way through the East German control stations, and then to each other on the other side, I experienced a discomfort I’d never known before.

We were being watched and controlled at every turn. Surveillance cameras were frequently in the mix. Armed, patrolling East German soldiers were visible at almost every turn.

In order to purchase items to take back with us or to eat or drink, we were compelled to use East German Deutschmarks that had to be spent (or lost) during our short visit. But, ironically, we learned that purchases were so cheap in the East, it was virtually impossible to spend all the money we had converted.

For lunch, we made our way to the old opera house at the Brandenberger Tor. It was probably one of East Berlin’s most prestigious grazing spots. We ate a first class meal.

I had a steak and a glass of wine, followed by dessert and a coffee. Claudia had a wonderful fish plate and salad, as well as wine and dessert. Our bill, including a big tip (not really necessary because service fees were included in the bill) was eye-popping. All of that came to no more than $20 U.S.! In New York or Los Angeles, the same meal would have cost at least $100 in 1989.

We spent the afternoon at Alexanderplatz, one of East Berlin’s largest shopping centers. It was chock full of stores and street activities. We purchased a few souvenir trinkets.

That afternoon, we realized that we still had a lot of money to spend, so we made our way to a downtown hotel near Alexanderplatz to have a drink and reflect together on our experience. At the hotel, we found a restaurant that we thought could be good for a cocktail or a refreshment. It was a large tea room, filled with locals, almost all of them seniors.

As the restaurant host escorted us on a long hike from the tea room’s entrance to a back seat by the window, it became immediately clear that we were being watched by virtually everyone in the place. Indeed, I distinctly remember the very loud hall becoming notably more silent as we made our way through.

Unlike everybody else there, we were young–a good 20 or 30 years younger than the crowd all around us.

We were also obviously an interracial couple: My fair-skinned European wife, Claudia with her light brown hair and big blue eyes; and me with my bronzed-colored skin, brown eyes, and dark curly hair.

And, above all, we were obviously from the West–or as the contemporary vernacular of the day would have it among the former communist-controlled citizenry, we were “Wessies”.

We could feel a combination of curiosity, fear and contempt land upon us as we made our way to our seats. Unwittingly, in that context, our couplehood and presence were a provocation. To say that our visit to the tea room amounted to about 45 minutes of mutual awkwardness would be an understatement.

For me, the uncomfortable tea room experience was another reminder of what living under communism in East Germany must have felt like. Conformity was the common denominator of how the authoritarian system of the East worked. Nonconformity was an invitation to rejection, discomfort, and as history subsequently revealed, in many cases, much worse.

Naïvely, when the West ultimately prevailed in the Cold War that dominated the post-WWII era ending the 20th century, many including me thought that it would invite democracy and freedom as far as the eye could see. Certainly for the remaining years that I might have to walk the planet.

On that account, the immediate post-Wende years inspired me to start my own consulting firm specializing in creative economy and multicultural innovation, both in the U.S. and internationally.

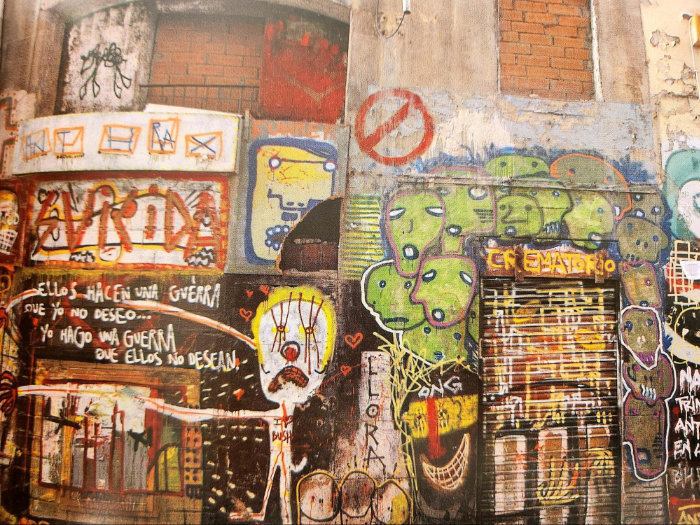

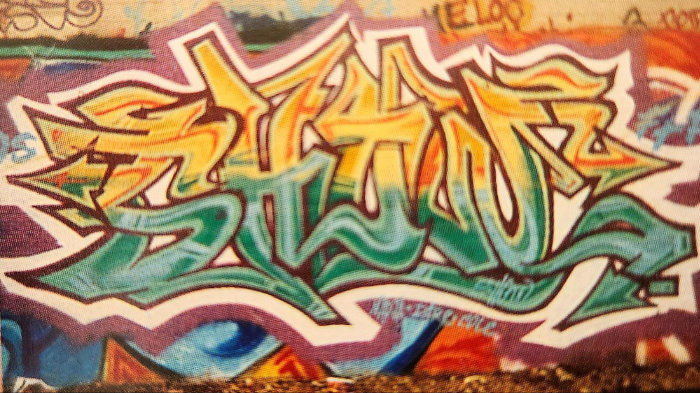

In the spirit of my love affair with the Berlin Wall experience and all that it had done to elevate my connections with art and democracy, I named my consulting firm Mauer Kunst. In German, Mauer Kunst literally means wall art. But in a broader sense it is roughly equivalent to the term graffiti.

For me, the phenomenon of graffiti throughout the ages has always embodied the spirit of democracy and a certain irreverence for authority and convention. It has always spoken to my inner quest for creative independence and diversity of thought and experience (things that I have always associated with open societies).

Here’s a brief panorama of graffiti from different parts of the world, from Nicolas Ganz’s “Graffiti World” (2009) and Mervyn Kurkansky’s and Jon Naar’s “The Faith of Graffiti” (1974).

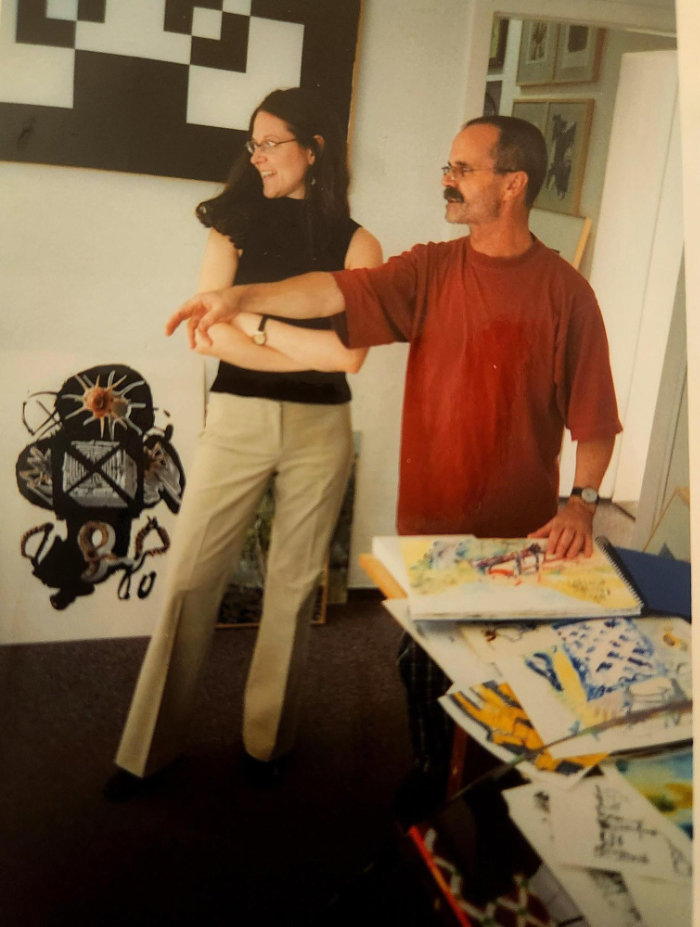

By the early 2000s, my experiences in Germany and especially at the Wall had also inspired me to explore and rediscover my own artistic passions. I produced a lot of original paintings and collage works. Ultimately that led me to affiliate with Jim Horton’s Gallery of Graphic Arts (GOGA) and to rent an art production studio of my own, both located on New York’s upper eastside.

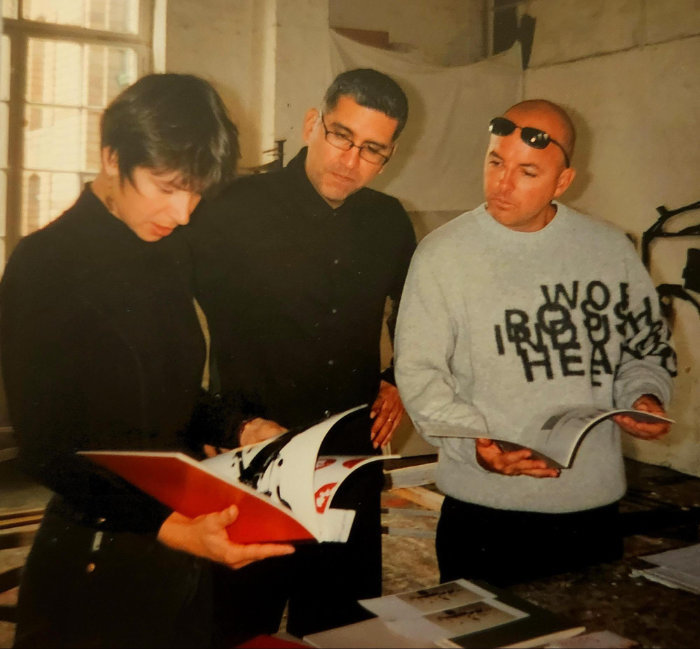

During this period, I participated in various group shows and mounted a major exhibition of my original works at GOGA. And Claudia and I traveled again to Berlin on multiple occasions, to exhibit my art and to meet artists and creatives in the East, like Pomona Zipzer and Reiner Poser.

In 2010, the evolving dream of promoting democracy and multicultural common cause further motivated me and Claudia to buy a 10 acre ranch on the California Central Coast and to join forces with the renowned artist Anne Laddon and her daughter Sasha Irving, to help establish Studios on the Park in downtown Paso Robles, CA.

My first project there was to recruit numerous at-risk kids and street youth to paint a mural celebrating the ten year anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. The project involved about 25 young people and it captured the community’s attention in a big way.

Those first decades of the 21st century were accordingly among the most creative and productive periods of my life. I painted, drew and exhibited many original works of art, I led community-building and multicultural youth art projects; and, building on art and creativity, I advocated in the community–at city halls, in the parks, in schools, at the local police department, and in regional media for a better way forward–a more inclusive and democratic way for everyone who made up our community.

These were worthy pursuits that moved the people involved to a sense of higher purpose beyond mere selfish and material pursuits. I thought this was both unquestionably humanistic, as well as patriotic work given the nation’s fast-changing demography and culture, and the emerging impacts on politics, society, and the economy of high technology and corporate concentration.

I did not foresee that my impulses in these directions, along with the rise of many even more major moves to diversify and democratize American institutions would be met by a generational backlash of white, christian conservatives. I did not anticipate that work that I and so many like-minded people were seeking to advance would come to be seen by many as somehow un-Godly and un-American.

I never foresaw the possibility in America of secret police forces aggressing and disappearing people who look like me, or political leaders at the highest levels disregarding federal court rulings on core issues of American civil rights and civil liberties.

I never imagined that authoritarianism and fascism, as it once existed in Germany and behind the iron curtain during the 20th century could ever take hold in the world’s leading nation and economy, to such an extent that I would no longer be able to recognize my own country.

I never dreamed that Claudia, my pretty, decades-long U.S. permanent resident wife would suddenly be separated from me at the border entries of American airports and required to pass through designated portals for non-citizens, much as we were separated nearly 40 years ago at the East German border in Berlin.

And, yet, here we are approaching the third decade of the 21st century, with America undeniably in the throes of a kind of authoritarianism and fascism that harkens back to the WWII and post WWII eras.

I am reminded, accordingly, of the vital role that artists have been called to play in past, similar epochs of world history, to lead us in a different and better direction.

In this connection, don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. Artists and the arts are a vital part of any living democracy. They are the mirrors of our collective humanity and our better angels.

Now is a time for artists to do even more than they usually do, to lift people up, to show them a better way forward, to challenge authority, and to inspire a lowering of the walls that continue to divide people.

On this occasion that commemorates the 36 year anniversary of the Berlin Wall’s demise, let’s all find new inspiration to join hands in support of our democracy, the arts, and our best traditions as a multicultural society.

Both history and the future are ultimately products of our collective will. Let us dream and act together in a way that rejects walls, divisive politics, short-sighted economics, and tyrants.

The very future of our civic culture and global survival are depending on us!