In 1999, while serving on the board of directors of the San Francisco Mexican Museum, I met Dr. Guadalupe (Lupe) Rivera Marín, daughter of the world-renowned artist and political activist Diego Rivera. We quickly became close friends, and my wife, Claudia and I began to share joyous times with Lupe whenever we found ourselves in Mexico City, San Francisco, New York or anywhere else we all might be hanging out at a given point in time.

During the early 2000s, Lupe and I partnered on many projects, including her efforts to develop public art programs and dialogs, especially on occasions that might honor the memory and legacy of her famous father. I facilitated her speaking engagements at places like the University of Vermont (where my brother, Gregory Ramos chaired the Theatre Department), a meeting of Hispanics in Philanthropy board members at the Ford Foundation in New York City, and a Philadelphia Mural Arts conference, which she presented at as a keynote speaker.

I also introduced Lupe to important U.S. figures in arts and culture, like the noted mural artist and public intellectual Judith F. (Judy) Baca, the New York-based El Museo del Barrio executive director Julián Zugazagoitia (currently CEO of the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City), and arts patron and Rockefeller family member Ann R. Roberts (whose father, former U.S. vice president Nelson A. Rockefeller had been a friend of Diego Rivera).

Reflecting on Lupe’s passing at age 98 just over a year ago, I am moved to share some background on one of our most rewarding collaborations to lift up the important work of socially- and politically-minded mural- and public artists. While Lupe’s notorious father Diego is widely (and rightly) considered one of the greatest painters and artistic figures of the 20th century, above all his accomplishments were his contributions to the great tradition of public mural painting, which informed so many of the most significant creative contributions of the 1920s-1940s to civic life in Mexico, the United States, and many other nations.

Building on this legacy, Lupe ended her last two decades of life seeking to celebrate and advocate for mural arts and artists, particularly efforts and leaders in the field that focused on needed economic, political, and social change. In this work, Lupe’s energies and passions were seemingly unlimited. She traveled wherever she was invited to speak and proselytize in support of the cause. On many occasions, she asked me to facilitate and/or accompany her efforts in this important work. And, so, I often bore witness to her sheer persistence and will, her tireless commitment to advancing her father’s legacy and the Common Good. It seems like we were only activating around this work a very short while ago. But a recent, close review of my records suddenly reveals that the passage of time has been considerable. And with my dear friend’s recent passing, I feel compelled to get my experiences with her in support of public art on the record, as my own years advance.

Indeed, it is hard to believe that it has been almost 20 years since I helped Lupe to shape and organize the May 16-18, 2006 Mural Painting in the 21st Century International Conference in Mexico City; or that it has been now fully two decades since I had a hand in informing that gathering’s birth at the 2004 Philadelphia Mural Arts National Conference on Mural Art, organized by Mural Arts founder Jane Golden and her able colleague, my friend Brian Campbell.

The June 3-6, 2004 National Conference on Mural Art was organized by the ingenious Jane Golden as a way to build a stronger mural arts community of practitioners and supporters across the United States. To mount the effort, which took place in downtown Philadelphia, Jane raised funds from Ford Foundation, the Pennsylvania Council of the Arts, and the Robert H. Smith Family Foundation.

She had recently commissioned the artist Delia King to undertake the restoration of a mural she had originally painted in 1990 with Dietrich Adonis, which was entitled: Tribute to Diego Rivera. Perhaps as a result, she was thinking about Rivera when she organized the 2004 national gathering; and, being Jane (always forward-looking and expansive in both thought and action), she decided to reach out to Lupe to invite her to speak. Lupe discussed the invitation with me and I urged her to do it. She said that she would, if me and Claudia, as well as my brother, the actor/director/playwright Gregory Ramos (who she adored) accompanied her down from New York City, where we all lived at the time. It was a no brainer to agree. So that’s what we did.

What a memorable experience it was to travel with Lupe to Philadelphia for the Mural Arts gathering and to meet Brian Campbell there. Brian had been the guy behind the scenes making it all happen; and he served as my principal contact in the lead-up to the event opening, where we finally met and got Lupe connected to Jane.

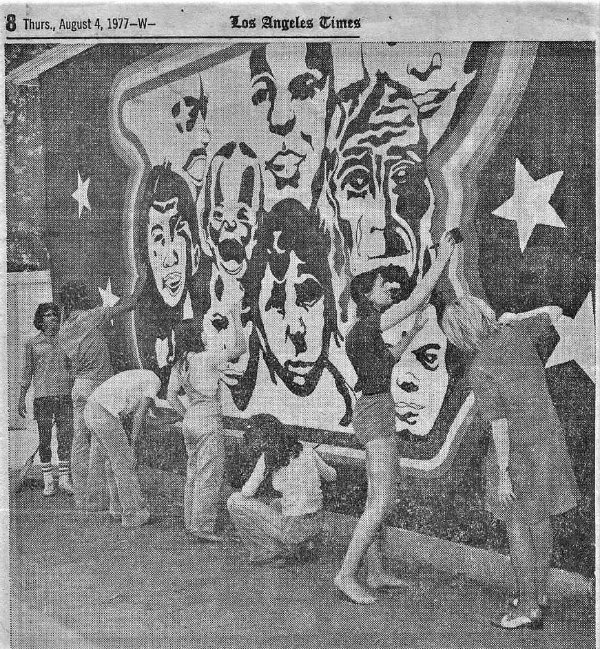

The Philadelphia conference is also where I had the opportunity to meet and introduce Lupe to Judy Baca, founder of the Venice, CA-based Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC), and the renowned muralist who conceived and led the Los Angeles River Basin Mural Project known as The Great Wall of Los Angeles in the mid- to late-1970s, when I began my own journey as a mural painter at West Los Angeles University High School.

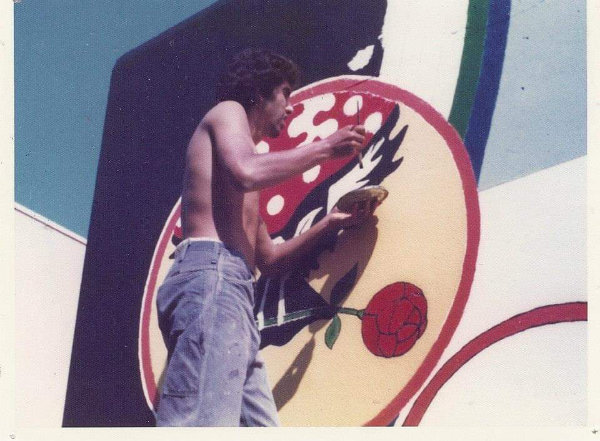

Me rockin’ the scaffolds at West Los Angeles University High School, as initiator of the UniHi Mural Project, April 1977

It was fascinating for me to be meeting Jane and Judy, two women whose work decades prior had made a large impression on my own public art inclinations. In 1976, while living and working in Los Angeles, Jane completed an iconic public mural called Ocean Park Pier at the corner of Ocean Park Boulevard and Main Street in Santa Monica, near where I grew up. Every time I went to the Santa Monica Beach, which was often during my teen years, I would pass and observe that impressive work.

On the other side of town, near Olvera Street, where my father, Sal Ramos and my uncle, Jay Ramos owned retail operations, Judy was laying down what is unquestionably the nation’s most significant and impressive public mural, The Great Wall. It is an epic depiction of California’s sordid history of race relations and economic development, which runs along the Los Angeles River in multiple story boards extending altogether over 2,750 feet!

While in Philadelphia, we spent time with Jane and Judy outside of the conference proceedings, to get out into the community and to show Lupe Jane’s Tribute to Diego Rivera mural, located at 27th and Mt. Vernon Streets in the central city’s Spring Garden neighborhood. Lupe loved the mural and enjoyed the time getting to know Jane and Judy a bit more in private. We also visited a nearby middle school, where Lupe and I took some time to exchange with the students studying art there, most of them gifted and dynamic African American youth.

Even more than at the Mural Conference, Lupe lit up when surrounded by the Philadelphia public school students that we met. They were all very talented, fun and eager to learn. But only one or two of the students had ever heard of Diego Rivera; so, Lupe took extra time to tell them a little something about her father, the late Master, in order for them to maybe want to learn more about Mexican and other multicultural artists who stood strong for important causes beyond art, like international labor and human rights.

Images of our day trip to the Tribute to Diego Rivera mural and a nearby public middle school, Philadelphia, PA, 2004

Back at the National Conference on Mural Arts the next day, Judy and Lupe made remarkable speeches. Judy presented a most informative discussion on the emerging uses of technology to render larger, more complex and more visually-pristine mural and public art works than had ever been possible before. At the same time, she also issued a very insightful warning about the encroaching legal and commercial interests of private sector giants, like the advertising behemoth Clear Channel, that were actively discouraging — even censoring — the use of public space for creative and social art. Their goal: to make more room for selling merchandise and services on billboards and other advertising platforms in the public square. (Judy’s warning was clairvoyant, as the problem has become even more daunting in recent years.)

Lupe gave her own rousing speech to conclude the convening. In her remarks, she issued a call to action for artists and creative economy leaders across the United States and the world to redouble their efforts to address social and political issues of the day in all of their work and public endeavors. She spoke passionately about her father’s commitment to using art for the Common Good, and especially on behalf of those in society who had the least economic, political, and social power.

In closing, Lupe announced, to my great surprise (and, later, I learned to hers as well) that she wanted to invite everyone assembled at the National Conference on Mural Arts in Philadelphia to Mexico City in 2006. She wanted them to gather with Mexico’s leading mural artists and other mural arts leaders from across the world, to carry the conversation forward in a large and memorable way. She declared that it was vital for mural artists across the globe to develop a more formal network and capacity to encourage mutual support, advance best practices, promote enabling public policies, and establish more robust funding streams to make consequential mural and public art an indelible feature of civic discourse and cultural economy in the 21st century.

Everyone left the Philadelphia conference renewed and fired up for the sequel gathering that Lupe promised. But to say that we had no predating capacity or plan to make it happen would be an understatement. Lupe had only recently begun talking about creating some kind of a vehicle to promote work of this sort to honor the legacy of her late father. What’s more, she had no real money behind it, nor any staff or program to speak of. So we began talking about the formation of a Diego Rivera Foundation and raising funds to support its first major public program: the 2006 Mural Painting in the 21st Century International Conference in Mexico City.

We subsequently bolstered our prospects for success in mounting a worthy follow up to the Philadelphia conference with the essential support of Lupe’s son, the talented Mexican filmmaker Diego López Rivera, and a team of allies including Judy Baca, Jane Golden’s close colleague at Philadelphia Mural Arts, Brian Campbell, and my longtime friend and colleague Nicolás Kanellos, founder of the University of Houston-based Arte Público Press (the leading publisher of Spanish language fiction, and Latinx culture and politics in the United States).

Over the course of the ensuing two years, with a planning grant that I secured from my friend Miguel Satut, then a program director at the W. K. Kellogg Foundation, our team met regularly by teleconference and occasionally in-person. Through Lupe’s and Diego’s efforts, we secured additional support along the way from various Mexican governmental agencies, like the National Council for Culture and the Arts (CONACULTA) and the Mexican Ministry of Public Education. We began putting together an exciting array of thematically-organized panel discussions and noted speakers; and we affectionately dubbed the gathering-in-the-making el Encuentro: In English, ‘the Meeting’ or ‘the Encounter.’

It was shaping up to be a monumental gathering, just as Lupe had promised in Philadelphia. But our planning effort was not without behind the scenes drama and heartaches. We hit some major, unanticipated snags along the way. In private conversations with my former colleagues at Ford Foundation, for example, it looked like I had successfully cleared the way for a significant grant that would have supported major cost centers for the Mexico City gathering.

However, after I confidentially informed Lupe of this promising prospect, not being able to contain her excitement, and in a momentary lapse of judgment, prior to the matter being formalized, she announced at a social gathering in Mexico City that Ford had made a major commitment to the effort. Unbeknownst to Lupe, the Foundation’s Mexico City representative was in attendance and well aware that the Foundation had not finalized a commitment. For various reasons, he was not a big Lupe fan. He did what he could to put our grant request on permanent hold. So, sadly, at the end of the day, the Ford grant never materialized.

In another moment of great disappointment, just a month before we were scheduled to convene the Encuentro, the Mexican Ministry of Education informed Lupe’s son Diego that it would be unable to provide the major funding it had initially projected. We surmised that the conservative then-president of Mexico, Vicente Fox, was likely not happy to learn that his education ministry was about to lavish major financial support on a project led by the daughter of the late communist champion Diego Rivera. For all intents and purposes, Lupe–a Mexican PRI loyalist and longstanding opponent of Fox and his ruling party, the PAN, was easy to consider a political rival of the prevailing administration.

Whatever the cause of the ministry’s reversal, the resulting last minute shortfall in revenue that it created was such that any other planning group would have been compelled to cancel the event. We seriously considered that option and commenced preparations to simply call the whole thing off. But, at the eleventh hour, after consulting with many of our projected speakers and guests, we decided to toss logic to the wind. We had heard from the many people we contacted across the globe that they were prepared to meet in Mexico City no matter what. The resilience and ‘can do’ attitude that our colleagues showed really bolstered Lupe’s spirits and resolve. She reared up and led the charge. Defeat would not be a consideration after all that our little team and our allies had done since the Philadelphia gathering to offer a global follow up conference at a high level of dialog and substance.

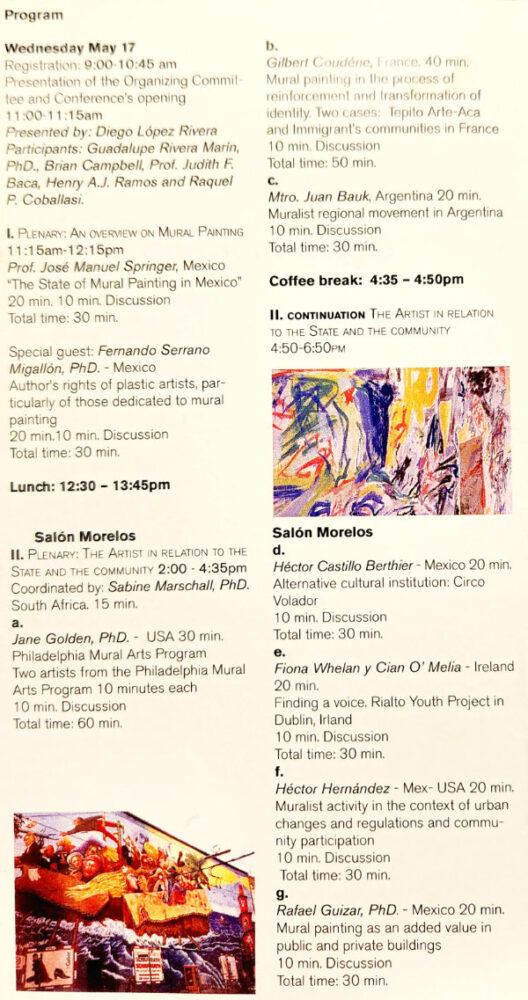

As it turned out, we absolutely made the right decision to proceed. The Encuentro was a large success. Over the course of its 3 days in duration, from May 16-18, 2006, nearly 200 mural arts practitioners, scholars and champions participated, including some of the most important and consequential public art practitioners and champions in the U.S. and around the world. In addition to Judy Baca and Jane Golden, participants and presenters included luminaries like Australian artist and muralist Geoff Hogg, South African cultural heritage scholar Sabine Marschall, German muralist Klaus Klinger, Dublin-based artist, writer and educator Fiona Whelan, and UK-based art historian and muralist Desmond Rochfort.

During our interactions, we produced nearly 50 informative conference sessions and workshops. We conducted our business with state-of-the-art language interpretation technology and the support of simultaneous translators working in English, French, German, and Spanish. We also articulated a comprehensive international agenda for mural arts practice and policy, that I captured in a detailed summary of the proceedings (included in bold at the close of this document); and that I reported back verbally to the assembled Encuentro participants at our gathering’s conclusion.

The substantive and dynamic exchange that we supported in Mexico City was subsequently reported to a broad international readership by Robin Rice of the Philadelphia-based University of the Arts in her excellent summary article published in the Fall/Winter 2006 edition of Public Art Review.

The program guide for the Encuentro

Various images of the rich Encuentro exchanges during May 16-18, 2006 in Mexico City

Upon closing my public report back to the Mexico City conference participants, I was able to bring Lupe and Diego to center stage and encourage all of the Encuentro attendees to express their heartfelt gratitude to our hosts. The assembled audience responded with a rousing ovation–loud cheers, roars, and gritos abounded that would have made Diego Rivera proud had he been alive to see his progeny representing his legacy and values in such style. It was one of the proudest moments of my life as an artistic creator, thinker and activist.

In the many years since the Philadelphia and Mexico City gatherings recounted here, I have remained in contact with the principal organizers of these events; and I have continued to champion multicultural arts issues, causes, and projects. Last month, I had the opportunity to visit Philadelphia where I shared a wonderful dinner with Mural Arts founder Jane Golden and her husband, the filmmaker Tony Heriza (who video recorded important segments of the Mexico City Encuentro), as well as Brian Campbell. At our dinner meeting, which included my wife Claudia and our longtime friend, the scholar and concept artist Sheryl Oring, dean of the University of the Arts Department of Art, Brian reminded me of an additional important connection linking Diego Rivera to the City of Brotherly Love–Philadelphia…

As fate would have it, on March 31, 1932,the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Philadelphia Grand Opera premiered Carlos Chávez’s symphonic ballet, Horsepower [H.P. orCaballos de vapor]. The legendary conductor Leopold Stokowski presided over the orchestra pit. Catherine Littlefield choreographed the dance elements; and none other than Diego Rivera designed the costumes and the sets. It was the one and only public performance of HP, ever. Widely misunderstood by the high-class American audience of industrialists, bankers, and arts-mavens of the time who saw it, the work was universally panned. But asLos Angeles Times culture columnist Carolina A. Miranda wrote in October 2022, HP and Rivera’s interpretive contributions were in many ways well ahead of their time:

[T]he ballet — which appeared for one night only, failing to make much of an impression on the critics. (John Martin of the New York Times described the choreography as consisting “almost exclusively of nervous bits.”)…The story of “H.P.” may seem like a footnote. But embedded within it are ideas that make the show as a whole an intriguing enterprise at this moment. Amid the shimmying fruit was a character called “The Man” (interpreted by Russian dancer Alexis Dolinoff), who represents an intriguing hybrid: a biracial man who is also part machine and whose costume drew from Yaqui deer dancers as well as elements of industrial design. The Man is a sci-fi mestizo — and a prescient precursor to the machine-enhanced Mexican laborers of filmmaker Alex Rivera’s 2008 thriller “Sleep Dealer.”

Costumes from HP were recently displayed at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s highly acclaimed retrospective of Rivera’s major works, entitled Diego Rivera’s America. The Rivera exhibition at SF MoMA was heavily informed by Will Maynez, a friend who is the longtime custodian of the Rivera mural at City College of San Francisco called Pan American Unity.

HP costume displays at SF MoMA exhibition, Diego Rivera’s America, 2022-2023

Ironically, Will and I met for the first time at the Mexico City Encuentro in 2006. Brian Campbell met Will there as well. Over the last couple of days, the three of us have been in communication about Brian’s interest in restaging the HP ballet in Philadelphia in late March 2032, to mark the 100 year anniversary of its one and only public performance in that same city. Could this be our friend Lupe Rivera Marín calling from Heaven with our next assignment?

Mexico City ‘Encuentro’ Summary

The International Mural Art Encounter was convened in Mexico City during May 16-18, 2006. The Encounter was organized by the Diego Rivera Foundation in collaboration with Arte Público Press of the University of Houston, TX, the New York creative advisory firm Mauer Kunst Consulting, the Philadelphia, PA-based Mural Arts Program, and the Social and Public Art Resource Center of Los Angeles, CA.

This gathering, one of the only global convenings of its kind ever assembled, brought together nearly 200 mural arts practitioners and community activists, government officials, creative consultants, journalists, scholars, and youth leaders from Mexico, the U.S., Europe, Latin America, and Oceania.

This important assembly was inspired by a June 2004 National Mural Arts Conference organized by the Philadelphia Mural Arts Program with major support from the Ford Foundation. Key sponsors of the Mexico City gathering included the W. K. Kellogg Foundation, the Mexican Federal Education Department, the Mexican Council of Arts and Culture, the Office of the Mexican President, the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, and the Jesus Reyes Hercóles Cultural Center of Coyoacán, Mexico.

Following are the essential observations, discussion highlights, and agreements that resulted from the meeting as presented at the convening’s close by Mauer Kunst Consulting principal Henry A. J. Ramos, a member of the Mural Art Encounter organizing committee.

• Our initial reception and panel commentaries set the tone for our international gathering. We acknowledged by our wide diversity that mural art is indeed a world phenomenon.

• Presentations by Mexican experts Dr. Guadalupe Rivera Marín and Professor José Manuel Springer reminded us of the deep traditions of muralism, and Mexico’s special influence on 20th Century world culture and practice in the field.

• We considered mural art’s evolution beyond paintings on fixed spaces, reflecting on its evolution into allied forms of expression: sculpture; virtual technologies; landscape architecture; housing; and urban redevelopment – often in mobile and replaceable forms.

• Our deliberations reminded us that mural art is a practice with a purpose: that our tradition is one of social activism and civic engagement in the interests of promoting humanity and nature over the individual and materialism. We talked about “giving a voice to the voiceless.”

• Our day two opening plenary speakers – Jane Golden, Gilbert Coudene and Juan Bauk – introduced us to the topic: “The Artist’s Relation to the State and the Community.” They helped us to chronicle how the civic power, practice, and reach of muralism is being developed today in places as diverse as Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Lyon, France; Quebec, Canada; and Argentina.

• From their presentations, we saw how mural art is extending its influence in contemporary context to important constituencies of historically-excluded groups: at-risk youth; immigrants; incarcerated prisoners; and other disenfranchised peoples; as well as historically-divided communities conflicted by racial-ethnic, religious, and other tensions.

• We discussed the essential importance of involving community members not merely in the completion of mural projects, but also in decision making about the content that such projects ultimately reflect.

• We reminded ourselves, at the same time, about the ethical imperatives of mural artists to lead on the major issues of the day and to pursue our work in a consistently-principled way – one that champions democracy, human rights, and social responsibility.

• Juan Bauk shared a list of enumerated ethical and artistic principles that he and his colleagues incorporate in Argentina in order to promote and exercise public leadership through their work. We agreed that this is a concept we may wish to consider developing and adopting at some point at the international level.

• Our discussions expanded on these themes. Eight sub-theme sessions from a range of thoughtful presenters underscored fundamental questions about best practice. Some of the key issues surfaced included:

1. integrating new voices and forms into the field (e.g., youth and graffiti artists and works with important political points of view);

2. striking the proper balance between exercising leadership on issues, and listening to and honoring sometimes-differing community perspectives;

3. addressing the growing influence of large private corporations on mural arts funding and content control; and

4. reacting appropriately and effectively to recent declines in public support and community engagement relative to our work.

• Fiona Whelen and Cian O’Melia talked about comprehensive efforts to engage youth in Dublin, Ireland through a broad range of public art activities, putting muralism and public sculpture projects at the center, but complementing them with allied work extending to performance art and music.

• Sabine Marschall addressed the recent development in South Africa of a major campaign – the South “C” Mural Project, which has radically shifted practice in that nation from a more grassroots, community-driven model to one that is more artist-centered and commercialized. She raised important questions about the implications of such a shift for that nation’s newly-emerging, Black-controlled democracy.

• Dr. Isaka Shamsud-Din spoke from his experiences in Portland on the essential responsibility of modern mural artists to “bear witness” to the historical presence, contributions, and humanity of society’s most forgotten people, their struggles for justice, and their collective vision for a better world.

• Brain Nissen reflected on the value of evolution in the means and imagery that mural and public artists project, and the field’s important role in raising awareness at the most profound levels of consciousness.

• We concluded our second day of sessions with an important conversion on the prospective value of formalizing an international network for mural artists.

• On balance, participants expressed a general agreement that such a development would be timely and could help to advance the field in various ways, by increasing prospects for:

1. networking/exchange;

2. knowledge dissemination about our work; and

3. movement coordination/support.

• Judy Baca of the Social and Public Art Resource Center in Los Angeles spoke about the wisdom of starting with virtual community-building strategies that are both economical and easily-implemented, including:

1. an internet community with common links to all of our respective websites; and

2. a rapid deployment communications network that, through periodic exchanges and alerts, could help us all to mobilize around important public issues and campaigns.

• Still others felt it also essential to build towards a more-than-virtual association of some kind – one that could help to organize and inform more convenings like this one, and ultimately facilitate field development and sustainability efforts at the global level.

• Most agreed however, that starting small amongst ourselves, step by step, makes most sense.

• London-based Jeanne-Marie Eayrs volunteered to develop a comprehensive contact list of Encuentro participants, to facilitate forward movement on all fronts.

• On our third and final day together, we re-assembled to consider important additional questions:

1. promotion and financing of cross-cultural projects;

2. the evolving politics of muralism and artist’s rights;

3. advancements in education and training in the field; and

4. the conservation and restoration of mural and public art works.

• On the topic of “International Finance and Inter-Cultural Projects” we agreed that financing issues clearly loom large as a challenge for our field.

• While some, selected programs have developed to become significant, well-financed, and well-staffed organizations, most mural art projects and organizations are under-resourced and stretched for sustaining support.

• We acknowledged that a large part of the problem is the progressive political content of much of our work, which is inherently discomforting to people and institutions whose ideological outlooks and material interests are in conflict with our own.

• Klaus Klinger of Düsseldorf, Germany suggested building on Judy Baca’s ideas of the previous day to develop a global virtual community; to lift up information-sharing on fund raising ideas and best practices.

• Kathleen Farrell of Chicago recommended increasing our professionalism as a means of expanding prospects for project and organizational financing. She urged efforts to develop a stronger public sense of our work’s legitimacy and community value-add by:

1. developing standards in contracting, fee scales, and employment practices; and

2. preparing and circulating the highest quality proposals and products possible.

• Like several earlier speakers, Professor Geoff Hogg of Australia underscored that, often, especially when working cross-culturally, allied art forms can complement in important ways the essential messages and purposes of muralism: sculpture, dance, and music.

• Berlin, Germany-based practitioner Don Karl reminded us that progressive mural artists also have a role to play in challenging authority on the far left, in places like Cuba (where he has lived and worked in recent years): in short, underscoring the essential responsibility of mural arts leaders to stand for and with people, rather than institutions and particularized interests.

• On the topic “The Politics of Mural Arts and the Rights of Artists,” New Zealand-based practitioner-scholar Dr. Desmond Rochfort, Judy Baca, and San Francisco attorney Brooke Oliver revealed how political issues and rights are among the most important matters facing public artists today.

• Even when there are laws that ostensibly protect our freedom of speech and even when our government systems claim to be democracies, we find more and more that we must fight for our rightful voice, our rightful space in the public discourse.

• Joe Cotter from Portland spoke to concerns about pending litigation in Oregon related to the large corporate interest Clear Channel.

• The risk of this litigation for mural artists everywhere eventually is to reduce – and possibly eliminate to a mere sliver – the status of public space for the common good, in favor of a highly-corporatized notion of the commons.

• With many of the increasingly contentious issues that inform our times, reaction and even the threat of repression and violence against many of us is becoming a very real danger in more and more places.

• Going forward, we must defend the integrity of our rights, our intellectual freedom, and our physical safety using various means, including:

1. collective solidarity;

2. legal defense;

3. community organizing; and

4. public engagement.

• We must especially guard against the private forces of censorship that mark our times, through vigilance, awareness, and mutual support.

• As Desmond Rochfort reflected at the outset of his eloquent remarks, we must expand appreciation that, fundamentally, murals are not commodities that can be conventionally understood in the framework of modern economies.

• We cannot forget the inherently collective nature of this work, dating back to the earliest cave renderings in recorded human history.

• On the topic of “Education and Field Capacity Building,” Judy Baca revealed important new technical developments and possibilities for muralism worldwide, and their profound emerging impacts on:

1. application;

2. imagery;

3. economy;

4. transportability;

5. durability;

6. information exchange; and

7. field building.

• These new capabilities raise important questions: How will we utilize them and to what ends? Will increased capacity result in a better product? Will it support or diminish the field’s democratic and inclusive tendencies? – questions that are remarkably similar to those raised earlier by Sabine Marschall in her recount of recent issues and trends in South Africa.

• Julio Carrasco Bréton of Mexico raised important questions about the continuing traditions of Latin American muralism in the face of shrinking government support and declining status of the field in important quarters, coupled with a growing bureaucratic mentality among country leaders in relation to public art.

• Mexican-based artist and scholar Patricia Quijano and Geoff Hogg surveyed the education and training needs of muralists in the field, revealing a still-fertile ground for much more to be done in this area.

• A key aspect of the need concerns more formal education and training program offerings that can help to educate and develop new practitioners through a combination of theoretical and practical curricula.

• The challenge is to make these programs relevant to both students and the larger community; and also to ensure that they open up meaningful pipelines to application and employment opportunities for participants.

• In group discussion, we agreed that international intellectual and practical exchanges involving mural artists are essential to develop and support.

• We closed our discussions focusing on the important topic: “The Conservation and Restoration of Mural Art.”

• On this topic, our Mexican colleagues Walter Boelsterly and Margarita López Fernández underscored the importance – indeed the urgency – of prioritizing conservation as a field practice and as a point of advocacy in our work.

• Still far-too-little public and private funding is directed to conservation, with grave impacts on the field by virtue of the actual and prospective loss of highly important mural works.

• Boelsterly and López Fernández urged us to recall that we have a profound responsibility to work towards changing the public mindset that suggests we achieve more by saving our tax dollars versus saving these great works.

• They also spoke to the need to educate public emergency agencies, such as fire departments, to adopt more mural-friendly policies in order to save works that are sometimes unnecessarily lost during fires or earthquakes, largely out of ignorance.

• Finally, in closing, we concurred that we must expand support for mural-related conservation and restoration research (as well as innovation and practitioner education on conservation best practices), drawing especially on proven expertise in the field and artists themselves wherever possible.